The heart of mermaid lore in the West is one of the great fairy tales, as told by Hans Christian Andersen: The Little Mermaid. She is much beloved in Europe; her statue in Copenhagen is a point of pilgrimage for travelers to Denmark.

It’s been a long, long time since I read the original. My memory of it is a little warped by the Disneyfied versions (which I will talk about in the next article or two). I remembered it as a tragedy of a mermaid who gave up everything for a prince who didn’t even know what she’d done, or why she did it.

That is definitely part of it. Like the selkie story, it casts a dark light on the role of women in Western culture. I’ve read somewhere that for boys, puberty expands their horizons, but for girls, it sharply contracts them. Boys grow up to rule the world. Girls grow up to be ruled by men.

For the Little Mermaid, who doesn’t even have a name (though to be fair, neither do any of the other characters in the story), puberty is both a rite of passage and a death sentence. She’s the youngest of six daughters of the king of the sea. She’s shy and quiet, and of course exquisitely beautiful, with the loveliest voice in the world. Each of the sisters, on her fifteenth birthday, is finally allowed to swim to the surface—to come out, as Jane Austen fans might say.

The youngest sister is both jealous and impatient, but she doesn’t rebel. She’s fascinated by her grandmother’s stories about the human world (there’s no mother in this story; she’s never even mentioned—which is its own kind of interesting). She listens eagerly to her sisters’ accounts of their first time out. They all lose interest in a few days or weeks, and come back home to the sea.

Buy the Book

Under the Smokestrewn Sky

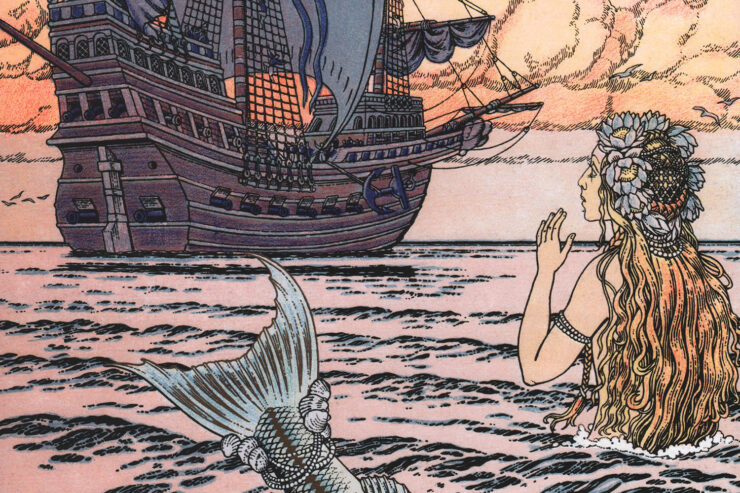

When at long last she has her own birthday and her own coming out, she emerges as a ship passes by. On it, a beautiful young prince is having his own birthday, his sixteenth. She is enthralled.

A storm rises in the night, and the ship is wrecked. She searches desperately for the prince, because she knows that humans can’t live under the sea. Finally she finds him, carries him up to the air, and brings him to land.

She leaves him there, to be found by a group of young human girls. He wakes, and believes that the leader of the girls is his rescuer; he never sees the mermaid who actually saved him, nor knows what she did.

The rest plays out in the tragic mode: the mermaid’s obsession, her journey to the lair of the sea witch, the terrible bargain she makes. In order to be with the prince, she gives up her whole life in the sea, her fish’s tail, and her beautiful voice. Every step she takes on her human feet is pain. And if she fails to win his heart and his hand in marriage, if he marries another, on the very next day she’ll melt into sea foam. There is no going back from this. Once she’s paid the price, she’s bound forever.

What I had not remembered was the real reason why she does this. She is fascinated by the human prince, and she does seem to love him, or at least to like him very much. But it’s not romance she’s after. It’s something much more powerful.

Mermaids, her grandmother has taught her, do not have immortal souls. They can live for three hundred years, but when they die, they melt into foam and vanish into the sea. Humans, on the other hand, live much shorter lives, but their souls endure forever.

That’s what the mermaid sacrifices everything for: to have a soul. The only way she can get it is to marry a human man. Then part of his soul will enter into her, and she will go wherever souls go after the body dies.

Because she can’t speak, she can’t tell the prince that she’s the one who rescued him. He treats her as a pet, indulges her like a child, and fails to see her as a potential wife. She still dares to hope, because the girl who found him on the beach was apparently a priestess in a temple; she’s cloistered from the world, and it’s unlikely the prince will ever see her again. All the mermaid has to do, she thinks, is be patient, and he’ll come to his senses and marry her.

But when he sails to a neighboring kingdom, the princess of that kingdom turns out to be the girl from the beach, and that’s it. That’s all he thinks he needs to know. He marries her, and the mermaid faces her doom.

But again, I had not remembered the actual ending. First, that her sisters come to her and tell her they’ve struck a bargain with the sea witch. If the mermaid kills the prince with the knife they’ve brought, his heart’s blood will restore her to her former self, fish’s tail and all, and she can go back home.

She can’t do it. She can’t take his life. She falls into the sea, and melts—but her consciousness doesn’t die. She finds herself surrounded by spirits of air, who tell her that because she’s made such great sacrifices, she gets a second chance. Three hundred years as a spirit of air, doing good in the world, and in the end, she’ll have earned an immortal soul.

It’s not a tragedy after all. It’s not a romance, either. The prince is a means to an end. When that fails, she still gets what she wants, though she has to be patient, and work at it.

It’s quite a Victorian conclusion, and pretty openly Christian, though the story talks about temples (but also about church bells). Good girl works hard and does good works and wins her way to heaven. She doesn’t have to get married (i.e., have sex) to get there. There’s a second, longer and probably harder, but just as effective way. She becomes a disembodied spirit, a creature of pure (good)will.

Andersen pulls out all the stops on his scene-setting. He describes the sea-king’s palace in loving detail. The sea witch’s realm is suitably horrific, complete with predatory sea creatures, whom the mermaid must pass both coming and going, and try not to be eaten. We see the land and its flora and fauna as a mermaid would see them: birds as a peculiar kind of airborne fish, and trees as dry-land kelp.

We even get a glimpse of mermaid fashion. Mermaids decorate their tails with oysters, each of which contains a pearl. The grandmother, the dowager queen, wears more oysters on her tail than anyone else; she’s quite firm about her place in the hierarchy. She wears twelve. Other high-ranking mermaids only get six.

When the youngest mermaid gets ready for her birthday journey, the grandmother adorns her with eight oysters, two more than usual. When the mermaid protests that they pinch, her grandmother says, essentially, Beauty is pain. Swim and bear it. Which is a foreshadowing of the bargain she’ll make with the sea witch, trading her tail for feet and pain.

It’s all, ultimately, to win herself an immortal soul. By Victorian and Christian standards, that’s the best of causes.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.

I was already beyond this tale prior to the Disney animation, but I must have read a shortened, simplified version, because I remember nothing about the importance of a soul. For some reason, I do however, have a clear memory of the oysters and their discomfort.

Poul Anderson’s The Merman’s Children is based upon this story. As I recall, all of the Danish merfolk gain souls by accepting baptism, with a couple of exceptions, so it’s not all that close to Hans Christian Anderson’s version.

@1 I may have read abridged versions as a kid, too. I found the full version online, and it’s got a whole lot going on that I had not remembered. Not really surprising if the abridgers took out the religious aspect, especially if they were aiming at a US audience. It changes the story in some pretty significant ways.

@2 I see I’d better reread The Merman’s Children. Thanks for the rec! It ties in nicely with the films I’ve been watching.

The ebook is on sale right now, fyi.

Noteworthy here, is that Anderson was responding to an even older story: Undine. I bought it for the illustrations (Arthur Rackham, a good reproduction) but was struck by the story. Undine is old. Undine reads old. Undine, the character, is very much a fairy. capricious, awkward, sometimes heartless, but trying to do good, and with no deliberate malice to her at all. She was raised with humans so that her human background might gain her the chance to marry a human man, and so gain access into heaven- for God created such sprites as she to be stewards of the mortal world, and they cannot endure sperate from it as mortals can. Undine is a character. The knight she marries is a character. The Other Woman is a character. No one is a means to an end- but Undine’s soul and salvation are wholly dependent on outward factors and the choices of others, and Undine’s kindness leads to the unravelling of all that everyone had hoped for. And it is hard to say if after the Knight’s betrayal, Undine, who had married a mortal, still counted as mortal enough to die mortal’s death and enter into heaven with him.

If rereading Anderson’s Mermaid was interesting, especially for those who had forgotten the True ending- try Undine. Back to back, you can tell Anderson was arguing with Undine.

Carolyn Turgeon’s book “Mermaid: A Twist on the Classic Tale” tells the story from the POV of the girl who he mistakes for his rescuer – as well as from the mermaid. It’s a fascinating take on the characters.

There are times when Anderson hits even harder on some of the disturbing aspects of Christianity; we’re told at the end of “The Little Match Girl” that her pain was over because she was now with God. I don’t know whether this was Anderson’s personal conviction or whether he thought that the best way to sell fantasy was to hang a Christian drapery over it. This process is obvious in the successive edition of Grimms’, where a comparison shows the gratuitous bits of faith added in later versions, but AFAIK there’s only one known version of most of Anderson’s work.

@2: if I recall correctly, people think the merfolk gain souls with baptism, but we learn (spoiler) that they in fact lose one, when at the end, one who was baptized against her will fuses with the soul of a russalka and becomes a mermaid again.

@7 – Actually I misremembered the source for this book – it was another Danish story that involves a mortal and a mer, but the mortal was a woman and the mer male. There’s a plot summary here – https://goodman-games.com/blog/2022/12/02/under-the-sea-a-look-at-poul-andersons-the-mermans-children/

However, creaky as my memory is, I’m still pretty sure that the character who fused her soul with the rusalka was a mortal woman who’d taken up with one of the mermen. And the mers who accepted baptism said themselves that they had gained everlasting life in the Christian heaven (barring the commission of mortal sin).

@2, 7, 8 I snagged a copy of the ebook, so I’ll read it and see what Anderson (versus Andersen) actually wrote. Watch this space.

Please note that Christianity sees good works as the fruits of salvation and not its source. We have “all have sinned and fall[en] short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23) and can be saved only if we are “justified freely by [God’s] grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus” (Romans 3:24).

Tumblr is a fan of a queer reading of The Little Mermaid (I think Andersen was at least some sort of queer?). The helpless, futile, and painful love of the mermaid for the prince certainly offers room for it. Same with the transformation of self and the promise of salvation when you don’t get what you want.

@10 There is major disagreement on Good Works among the various denominations of Christians.

IIRC, Queen Victoria had nine children, which doesn’t suggest a profound objection to sex as such. She might have objected to adultery, but that is a betrayal of trust. Which she would definitely objected to.

She doesn’t have sex but when her tail is split into legs she bleeds, which at minimum reads like an allusion to female puberty. I’d remembered that — and the constant pain walking caused her — but not that her voice was taken by the sea witch actually cutting out her tongue, nor her transformation into a spirit of the air. That ending is a quite abrupt, infodumpy deus ex machina, even allowing how we’re in a fantasy world to begin with.

I also found it odd that the revelation of the neighboring kingdom’s princess as the mysterious, lovely young novice/priestess from the beach is the sort of twist usually reserved for the heroine of the fairy tale (or for her own inamorato).